UBC evolutionary biologist Judith Mank discovers diversity in nature — and celebrates it in people, too

Black seadevils are a wonder among sea creatures: the females are large, bulbous creatures with fleshy, glowing growths spurting from their heads to lure their mates and their dinner; the males are often tiny, toothless swimmers whose sole purpose in life seems only to be for carrying the sperm required for reproduction of the species.

Understanding the role of genetics in the evolutionary processes that can lead to such extreme differences between the sexes is one of the most fundamental and puzzling questions in the study of evolution.

It’s one that Judith Mank, an evolutionary biologist and Canada 150 Research Chair in Evolutionary Genomics, strives to answer.

“Most people take it for granted that males and females differ in their genetics,” says Mank, who joined UBC in 2019. “In some extreme examples, like the black seadevil and their cousins in the anglerfish family, the sexes of animals are so different that they were originally classed as separate species.”

Mank’s research seeks to understand the evolutionary pressures that cause these differences and how they are encoded within the genome. She is a leading expert in understanding how genomes determine both the physical and behavioural traits that classify the sexes among non-human species — everything from chickens to moths, trees and tropical fish.

“Genomic approaches and capacity have expanded enormously since the early 2000s,” she says, explaining that much of today’s advances in animal genomics are built upon the knowledge gleaned from the Human Genome Project (HGP). HGP was a multibillion-dollar international research exploration that mapped the human genome using (at the time) new advances in DNA and genomics technology.

“We can now sequence multiple individuals of a population within weeks and track evolution almost in real-time,” she says. “But because of that, we’ve learned that genomes are remarkably messy. So for researchers like myself, the difficulty — or the fun, depending on your perspective —now lies in figuring out how to find the signal of evolution in all that noise.”

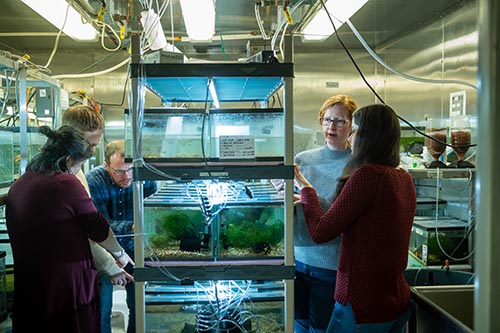

To find those signals, Mank looks to the diverse community of researchers at UBC’s Biodiversity Research Centre and the department of zoology.

.

“My colleagues at the university are absolutely remarkable — they’re brilliant, yet down-to-earth. UBC has a rich intellectual community and it’s exciting to be a part of it,” she says.

Mank celebrates diversity not only in her research but also in her research team; bringing together a range perspectives, skills, and life experiences

“My goal,” she says, “is to create an environment where everyone can come in with an open mind and feel comfortable asking for help from each other when they need it, and that there’s something valuable to learn when things don’t match our expectations.

“In research, as in life, there is so much to be gained by working together, learning from each other and solving problems collectively.”

Photographs for this story were taken prior to COVID-19 social distancing requirements.